Key Points

-

Provides an overview of the pharmacology of oral contraception.

-

Reminds general dental practitioners of the previous guidance given to patients taking oral contraceptives and antibiotics.

-

Educates dentists as to the recent changes in advice that should be given to patients taking oral contraceptives and antibiotics.

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to highlight a change in guidance relating to possible interactions between antibiotics and oral contraceptives. Until recently, dentists have been advised to warn women taking the combined oral contraceptive pill of the routine need to use additional contraceptive measures while taking courses of broad spectrum antibiotics. Recent guidance relating to this issue has changed and dentists may not be aware of this. This paper reminds dentists of the previous guidelines and related evidence, reviews the pharmacokinetics of hormonal contraception and presents them with the latest evidence-based guidance. This should change their clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Clinical scenario

A 24-year-old female attends your practice with a swollen face due to a dental periapical infection associated with the upper left first premolar. You obtain drainage by accessing the root canal, however, due to the facial swelling and the patient's associated malaise and reported pyrexia, you prescribe 500 mg amoxicillin to be taken three times a day for five days. Her medical history reveals she is taking the contraceptive pill. What implications does this have?

Previous recommendations

This is a very common clinical scenario faced by dentists on a daily basis and has been for many years. In 1994, the British Dental Journal published a paper reviewing the possible interactions between antibiotics and oral contraceptives emphasising the need for dentists to follow current national guidelines as part of good dental practice.1 At the time the guidance was that as a dentist you needed to warn the patient that the antibiotics prescribed to them may interfere with the contraceptive effects of the combined oral contraceptive pill and that additional contraceptive methods should be used while taking the antibiotics and for seven days after stopping.1 This advice was based on our understanding at the time and further publications reminded dentists of their professional obligations in this area and the possible medico-legal implications of not following current guidance.2 Various mechanisms for delivering the advice to patients, including a patient information leaflet, were suggested.

Hormonal contraception

There are two main types of hormonal contraception. These are the combined hormonal contraceptive and the progestogen-only contraceptive. Combined hormonal contraception contains an oestrogen and a progestogen component. When the amount of oestrogen and progestogen is fixed they are know as 'monophasic'. When the amount of hormone varies according to the stage of cycle, they are known as 'phasic.' The oestrogen component is usually ethinylestradiol although mestranol and estradiol valerate are sometimes used. The progestogen used can vary and includes desogestrel, drospirenone and gestodene. The oestrogen works by stopping ovulation. The progestogen works by thickening the cervical mucus, which prevents the passage of spermatozoa and thinning the endometrial lining, which prevents the implantation of an embryo. This combination prevents pregnancy. Combined hormonal contraception is available as an oral pill, a vaginal ring and a topical patch. The oral pills may be taken on a 21 day cycle with a 7 day break or taken continuously. The progestogen-only contraceptive is available as an oral pill, an intramuscular injection and an impregnated intrauterine device. The progestogen-only oral pills are taken on a continuous basis and prevent pregnancy by thickening the cervical mucus and thinning the endometrial lining. They are usually used when oestrogens are contra-indicated.

In 2006, 24% of all women aged 16-49 years were reported to be taking the combined oral contraceptive in the UK.3 It is considered 99% effective if taken according to instructions.4

Factors affecting the reliability of oral contraception include:

-

1

Diarrhoea and vomiting: vomiting and persistent, severe diarrhoea can interfere with the absorption of the combined oral contraceptive and progestogen–only contraceptive. If vomiting occurs within 2 hours of taking the contraceptive pill, another should be taken as soon as possible. Severe persistent diarrhoea lasting longer than 24 hours means that an additional method of contraception should be used for the duration of illness and for a period of time after recovery5

-

2

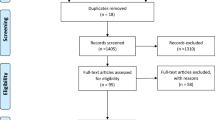

Interaction with enzyme-inducing antibiotics: combined hormonal oral contraceptives usually contain ethinylestradiol as the oestrogen component. Oral ethinylestradiol is absorbed from the small intestine and undergoes first-pass metabolism in the liver. Once conjugated with glucuronic acid, it is excreted into the bile and passes into the small and then large intestine. Hydrolytic enzymes produced by bacteria in the large intestine cleave conjugates of ethinylestradiol, which release it to be reabsorbed in the large bowel. These then enter the enterohepatic circulation (Fig. 1). The most important hepatic enzyme is cytochrome p-450 mixed function oxidase. Induction of this liver enzyme accelerates the metabolism of ethinylestradiol, which leads to less circulating levels. A reduction in serum levels of ethinylestradiol can lead to reduced efficacy of contraception. Rifampicin-like drugs (for example, rifampicin and rifabutin) are the only antibiotics that are enzyme inducers and have been consistently shown to reduce serum levels of ethinylestradiol6

-

3

Interaction with non-enzyme-inducing antibiotics: antibiotics that are not enzyme inducers can reduce colonic bacteria and therefore theoretically reduce enterohepatic circulation of ethinylestradiol. This could lead to reduction of combined oral contraception efficacy and result in unplanned pregnancy. Progestogen does not undergo enterohepatic recycling and hence has not been thought to be affected by antibiotics. This potential interaction, which has been a concern for dental practitioners for many years, has been influential in forming previous guidance and has continued to be reported in publications aimed at dentists.7

Antibiotics and dentistry

In 2010, general dental practitioners in England prescribed over 3.8 million items under the infections chapter of the British National Formulary.8 A study published in the British Dental Journal in 2011 showed penicillins accounted for 67% of antibacterial drugs prescribed by dentists in Wales. Other antimicrobials prescribed included clindamycin, macrolides and tetracyclines.9 In dentistry, enzyme-inducing antibiotics appear to be only very rarely used if at all, hence interactions of combined oral contraceptives with enzyme-inducing antibiotics is unlikely to be a problem (Table 1).

Current recommendations

There has been a recent change in the advice we should be giving patients in the given scenario.5 This new advice is evidence-based and follows a review of relevant studies looking at the interactions of non-enzyme-inducing antibiotics. Several studies and trials have looked at levels of ethinylestradiol in patients taking the combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP) and antibiotics and have not found decreased levels of ethinylestradiol or any change to the pharmacokinetics of ethinylestradiol.10,11,12,13

The World Health Organisation updated Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use in 2010 to include evidence-based guidance on contraceptive use and drug interactions.14 On the basis of this, in January 2011 the Clinical Effectiveness Unit of the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists) produced new clinical guidance which now states that 'additional contraceptive precautions are not required even for short courses of antibiotics that are not enzyme inducers when taken with combined oral contraception'.6 This new advice has been incorporated into the guidance given in the British National Formulary.5

If the antibiotics (or indeed the illness) should cause diarrhoea or vomiting, then the usual additional precautions relating to these conditions should be observed.

Conclusion

The recent change in the evidence base has implications for dentistry. When prescribing non-enzyme-inducing antibiotics to patients using combined hormonal contraception, the current guidance is that there is now no need to tell patients that they should use additional contraceptive methods while they take the antibiotics. For patients on any form of oral contraception, however, the guidance remains that they should be aware that additional contraceptive precautions are needed should they suffer diarrhoea or vomiting as a result of their illness or as a side effect of the antibiotics.

Whilst this is a subtle change in guidance, it has important potential implications for dental practitioners.

References

Gibson J, McGowan D A . Oral contraceptives and antibiotics: important considerations for dental practice. Br Dent J 1994; 177: 419–422.

Stephens I F, Binnie V I, Kinane D F . Dentists, pills and pregnancies. Br Dent J 1996; 181: 236–239.

The Office for National Statistics. Contraception and sexual health, 2005-06. London: ONS, 2006. Online article available at http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/lifestyles/contraception-and-sexual-health/2005-06/index.html (accessed March 2012).

Family Planning Association. Online information available at www.fpa.org.uk (accessed March 2012).

BNF. British National Formulary 61. London: Pharmaceutical Press, 2011.

Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare clinical guidance: drug interactions with hormonal contraception. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2011.

Seymour R A . Drug interactions in dentistry Dent Update 2009; 36: 458–460, 463–436, 469–470.

The NHS Information Centre, Dental and Eye Care Team, Prescribing Support Unit. Prescribing by dentists, 2010. England: NHS Information Centre, 2011

Karki A J, Holyfield G, Thomas D . Dental prescribing in Wales and associated public health issues. Br Dent J 2011; 210: E21.

Murphy A A, Zacur H A, Charace P, Burkman R T . The effect of tetracycline on levels of oral contraceptives. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991; 164: 28–33.

Abrams L S, Skee D M, Natarajan J, Hutman W, Wong F A . Tetracycline HCL does not affect the pharmakokinetics of a contraceptive patch. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2000; 70: 57–58.

Neely J L, Abate M, Swinker M, D'Angio R . The effect of doxycycline on serum levels of ethinylestradiol, norethindrone, and endogenous progesterone. Obstet Gynecol 1991; 77: 416–420.

Dogterom P, van den Heuvel M W, Thomson T . Absence of pharmacokinetic interactions of the combined contraceptive vaginal ring Nuvaring with oral amoxicillin or doxycycline in two randomised trials. Clin Pharmacokinet 2005; 44: 429–438.

World Health Organization. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 4th ed. Geneva: WHO, 2010.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Taylor, J., Pemberton, M. Antibiotics and oral contraceptives: new considerations for dental practice. Br Dent J 212, 481–483 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.414

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.414