Abstract

BACKGROUND: Adverse events resulting from medication error are a serious concern. Patients’ literacy and their ability to understand medication information are increasingly seen as a safety issue.

OBJECTIVE: To examine whether adult patients receiving primary care services at a public hospital clinic were able to correctly interpret commonly used prescription medication warning labels.

DESIGN: In-person structured interviews with literacy assessment.

SETTING: Public hospital, primary care clinic.

PARTICIPANTS: A total of 251 adult patients waiting for an appointment at the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in Shreveport (LSUHSC-S) Primary Care Clinic.

MEASUREMENTS: Correct interpretation, as determined by expert panel review of patients’ verbatim responses, for each of 8 commonly used prescription medication warning labels.

RESULTS: Approximately one-third of patients (n=74) were reading at or below the 6th-grade level (low literacy). Patient comprehension of warning labels was associated with one’s literacy level. Multistep instructions proved difficult for patients across all literacy levels. After controlling for relevant potential confounding variables, patients with low literacy were 3.4 times less likely to interpret prescription medication warning labels correctly (95% confidence interval: 2.3 to 4.9).

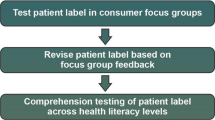

CONCLUSIONS: Patients with low literacy had difficulty understanding prescription medication warning labels. Patients of all literacy levels had better understanding of warning labels that contained single-step versus multiple-step instructions. Warning labels should be developed with consumer participation, especially with lower literate populations, to ensure comprehension of short, concise messages created with familiar words and recognizable icons.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Institute of Medicine. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. In: Kohn L, Corrigan J, Donaldson M, eds. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

Williams CM. Using medications appropriately in older adults. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66:1917–24.

Rollins G. Adverse drug events among elderly outpatients are common and preventable. Rep MedGuidelines Outcomes Res. 2003;14:6–7.

Georgetown University. Prescription drugs: a vital component of health care. Challenges for the 21st Century: Chronic and Disabling Conditions, Center on an Aging Society, Data Profile Series II 2002; 5: 1–6.

Institute of Medicine. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. In: Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer A, Kindig DA, eds. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2004.

Nichols-English G, Poirier S. Optimizing adherence to pharmaceutical care plans. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2004;40:475–85.

Kutner M, Greenberg E, Baer J. A First Look at the Literacy of America’s Adults in the 21st Century. National Center for Education Statistics: U.S. Department of Education; 2005.

Pharmex-Pharmacy Excellence, 1531 Airway Circle, New Smyrna Beach, FL 32168-5900, URL: www.pharmex.com.

Davis TC, Kennen EM, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV. Literacy testing in health care research. In: Schwartzberg JG, VanGeest JB, Wang CC, eds. Understanding Health Literacy: Implications for Medicine and Public Health. Chicago, IL: AMA Press; 2004: 157–79.

Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25:391–5.

Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The test of functional health literacy in adults: a new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:537–41.

MetaMetrics Inc. 1000 Park Forty Plaza Drive, Suite 120, Durham, North Carolina 27713. Lexile Analyzer: www.lexile.com.

Stenner AJ, Horabin I, Smith DR, Smith M. The Lexile Framework. Durham, NC: Metametrics; 1998.

Stenner AJ. Measuring reading comprehension with the Lexile framework. Paper presented at the 4th North American Conference on Adolescent/Adult Literacy; February 1996; Washington, D.C.

White S, Clement J. Assessing the Lexile Framework: Results of a panel meeting. NCES Working Paper Series, Working Paper No. 2001-08. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Research and Improvement; 2001.

Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:1049–60.

Davis CS. Statistical Methods for the Analysis of Repeated Measurements. New York: Springer; 2002.

McGee J. Writing and Designing Print Materials for Beneficiaries: A Guide for State Medicaid Agencies. HFCA Publication Number 10145. Baltimore, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Care Financing Administration, Center for Medicaid and State Operations; 1999.

Weiss BD. Health Literacy: A Manual for Clinicians. Chicago: American Medical Association; American Medical Association Foundation; 2003.

Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. Teaching Patients with Low-Literacy Skills. 2nd edn. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott; 1996.

Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Piette J, et al. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. JAMA. 2002;288:475–82.

Rudd RE, Comings JP, Hyde JN. Leave no one behind: improving health and risk communication through attention to literacy. J Health Commun. 2003;8(Suppl 1):104–15.

Baker DW, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, et al. Functional health literacy and the risk of hospital admission among Medicare managed care enrollees. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1278–83.

Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, Clark WS. Health literacy and the risk of hospital admission. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:791–8.

Williams MV, Baker DW, Parker RM, Nurss JR. Relationship of functional health literacy to patients’ knowledge of their chronic disease: a study of patients with hypertension and diabetes. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:166–72.

Wolf MS, Davis TC, Cross JT, Marin E, Green KM, Bennett CL. Health literacy and patient knowledge in a Southern US HIV clinic. Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15:1144–50.

Dewalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1228–39.

Kalichman SC, Ramachandran B, Catz S. Adherence to combination antiretroviral therapies in HIV patients of low health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:267–73.

Wolf MS, Gazmararian JA, Baker DW. Health literacy and functional health status among older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1946–52.

Einarson TR. Drug-related hospital admissions. Ann Pharm. 1993;27:832–40.

Morrell RW, Park DC, Poon LW. Quality of instruction on prescription drug labels: effects on memory and comprehension in young and old adults. Gerontologist. 1989;29:345–53.

Cline CM, Bjorck-Linne AK, Israelsson BY, et al. Non-compliance and knowledge of prescribed medication in elderly patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Failure. 1999;1:145–9.

Moisan J, Gaudet M, Gregoire JP, Bouchard R. Non-compliance with drug treatment and reading difficulties with regard to prescription labeling among seniors. Gerontology. 2002;48:44–51.

Beard K. Adverse reactions as a cause of hospital admission in the aged. Drugs Agency. 1992;2:336–7.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Health Communication. In: Healthy People 2010. With Understanding and Improving Health and Objectives for Improving Health. 2nd edn. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2000.

Farley D. FDA’s Rx for better medication information. FDA Consum. 1995;29:5–10.

Medication Guides for Prescription Drug Products. Code of Federal Regulations 2004 ed. Title 21; Pt 208: 111–114.

Status of Useful Written Prescription Drug Information for Patients; Docket No 00N-0352. Federal Register 65 (April 28, 2000): 7022.

Over-The-Counter Human Drugs: Labeling Requirements. Federal Register 64 (March 17, 1999): 13253–13303.

Svarsted BL, Bultman DC, Mount JK, Tabak ER. Evaluation of written prescription information provided in community pharmacies: a study in eight states. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;43:383–93.

American Pharmaceutical Association. Committee Policy Report on Health Literacy 2001–2002.

American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP Guidelines on Pharmacist-Conducted Patient Education and Counseling. Medication Therapy and Patient Care: Organization and Delivery of Services-Guidelines 1997;192–4.

Wogalter MS, Vigilante WJ Jr. Effects of label format on knowledge acquisition and perceived readability by younger and older adults. Ergonomics. 2003;46:327–44.

Sansgiry SS, Cady PS, Patil S. Readability of over-the-counter medication labels. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1997;NS37:522–8.

Dickinson D, Raynor DK, Duman M. Patient information leaflets for medicines: using consumer testing to determine the most effective design. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;43:147–59.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to report.

Dr. Wolf is supported by a career development award through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1 K01 EH000067-01).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Davis, T.C., Wolf, M.S., Bass, P.F. et al. Low literacy impairs comprehension of prescription drug warning labels. J GEN INTERN MED 21, 847–851 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00529.x

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00529.x