Abstract

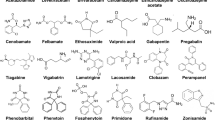

All psychotropic medications have the potential to induce numerous and diverse unwanted ocular effects. Visual adverse effects can be divided into seven major categories: eyelid and keratoconjunctival disorders; uveal tract disorders; accommodation interference; angle-closure glaucoma; cataract/ pigmentary deposits in the lens and cornea; retinopathy; and other disorders.

The disorders of the eyelid and of the keratoconjunctiva are mainly related to phenothiazines and lithium. Chlorpromazine, at high dosages, can commonly cause abnormal pigmentation of the eyelids, interpalpebral conjunctiva and cornea. It can also cause a more worrisome but rarer visual impairment, namely corneal oedema. Lithium can rarely lead to a bothersome eye irritation by affecting sodium transport.

Uveal tract problems are mainly associated with tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), typical antipsychotics, topiramate and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). TCAs, typical antipsychotics and SSRIs can all cause mydriasis that is often transient and with no major consequences, but that can promote closure of angles in susceptible patients. Topiramate has been frequently associated with a number of significant ocular symptoms including acquired myopia and angle-closure glaucoma.

Problems with accommodation are related to TCAs and to low-potency antipsychotics. TCAs cause transient blurred vision in up to one-third of patients.

Angle-closure glaucoma is a serious condition that has been mainly associated with TCAs, low-potency antipsychotics, topiramate and, to a lesser extent, SSRIs. When patients with narrow angles are given TCAs, they all appear to experience induction of glaucomatous attacks. Antipsychotics and SSRIs may lead to an added risk of developing angle-closure glaucoma, but only in predisposed eyes. Topiramate can lead to an allergic-type reaction whereby structures of the lens and ciliary body are displaced, which results in angle-closure glaucoma.

Cataractous changes can result from antipsychotics, mainly from high dosages of chlorpromazine or thioridazine. These two drugs, when used at high dosages and for prolonged periods, frequently cause lenticular opacifications.

Retinopathy has been shown to be related to high dosages of typical antipsychotics, mainly chlorpromazine and thioridazine. The frequency of occurrence of retinal effects seems to be proportional to the total amount of drug used over a long period of time.

Other visual problems of special concern are the ocular dystonias, other eye movement disorders, and decreased ability to perceive colours and to discriminate contrast. Ocular dystonias can occur with antipsychotics (especially high-potency ones), carbamazepine (especially in polytherapy), topiramate and, rarely, with SSRIs. Disturbance in various eye movements is frequently seen with benzodiazepines, antiepileptic drugs and lithium. Impairment in the perception of colours and the discrimination of contrasts has been shown to occur not uncommonly with carbamazepine and lorazepam.

Thus, typical antipsychotics, TCAs, lithium, benzodiazepines, carbamazepine, topiramate and SSRIs appear to produce most of the currently recognized ocular problems. Psychiatrists, ophthalmologists and patients need to be aware of and prepared for any medication-induced adverse effect. Early prevention and intervention can avoid most of the serious and potentially irreversible ocular toxicities.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Malone Jr DA, Camara EG, Krug Jr JH. Ophthalmologic effects of psychotropic medications. Psychosomatics 1992 Summer; 33(3): 271–7

Li J, Tripathi RC, Tripathi BJ. Drug-induced ocular disorders. Drug Saf 2008; 31(2): 127–41

Oshika T. Ocular adverse effects of neuropsychiatric agents: incidence and management. Drug Saf 1995 Apr; 12(4): 256–63

Hadjikoutis S, Morgan JE, Wild JM, et al. Ocular complications of neurological therapy. Eur J Neurol 2005 Jul; 12(7): 499–507

Stahl SM. Essential psychopharmacology: the prescriber’s guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005

Bond WS, Yee GC. Ocular and cutaneous effects of chronic phenothiazine therapy. Am J Hosp Pharm 1980; 37(1): 74–8

Johnson AW, Buffaloe WJ. Chlorpromazine epithelial keratopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 1966; 76(5): 664–7

Edler K, Gottfries CG, Haslund J, et al. Eye changes in connection with neuroleptic treatment especially concerning phenothiazines and thioxanthenes. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1971; 47(4): 377–84

Hansen TE, Casey DE, Hoffman WF. Neuroleptic intolerance. Schizophr Bull 1997; 23(4): 567–82

Elmar G, Lutz M. Allergic conjunctivitis due to diazepam [abstract]. Am J Psychiatry 1975; 132: 548

Pakes GE. Eye irritation and lithium carbonate [letter]. Arch Ophthalmol 1980; 98(5): 930

Lauf PK, Chimote AA, Adragna NC. Lithium fluxes indicate presence of Na-Cl cotransport (NCC) in human lens epithelial cells. 2008; 21(5–6): 335–46

Doughty MJ, McIntosh M, McFadden S, et al. Impression cytology of a case of conjunctival metaplasia associated with oral carbamazepine use? Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2007 Sep; 30(4): 254–7

Moeller JJ, Maxner CE. The dilated pupil: an update. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2007; 7(5): 417–22

Yu Y, Koss MC. Alpha(1A)-adrenoreceptors mediate sympathetically evoked pupillary dilation in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002; 300(2): 521–5

Szabadi E, Bradshaw CM. Autonomic pharmacology of alpa-2-adrenoceptors. J Psychopharmacol 1996; 10: 6–18

Lieberman E, Stoudemire A. Use of tricyclic antidepressants in patients with glaucoma: assessment and appropriate precautions. Psychosomatics 1987; 28(3): 145–8

Shur E, Checkley S. Pupil studies in depressed patients: an investigation of the mechanism of action of desipramine. Br J Psychiatry 1982; 140: 181–4

Schear MJ, Rowan AJ, Weiner JA, et al. Drug-induced myopia: a transient side effect of topiramate. Epilepsia 1990; 31: 643

Harsh AS, Henry SO, William BL, et al. Topiramate-induced acute myopia and retinal striae. Arch Ophthalmol 2001; 119: 775–7

Krieg PH, Schipper I. Drug-induced ciliary body oedema: a new theory. Eye 1996; 10 (Pt 1): 121–6

Fraunfelder FW, Fraunfelder FT. Adverse ocular drug reactions recently identified by the National Registry of Drug-Induced Ocular Side Effects. Ophthalmology 2004 Jul; 111(7): 1275–9

Hilton EJ, Hosking SL, Betts T. The effect of antiepileptic drugs on visual performance. Seizure 2004 Mar; 13(2): 113–28

Rhee DJ, Goldberg MJ, Parrish RK. Bilateral angleclosure glaucoma and ciliary body swelling from topiramate. Arch Ophthalmol 2001; 119(11): 1721–3

Costagliola C, Parmeggiani F, Sebastiani A. SSRIs and intraocular pressure modifications: evidence, therapeutic implications and possible mechanisms. CNS Drugs 2004; 18(8): 475–84

Patel OP, Simon MR. Oculogyric dystonic reaction to escitalopram with features of anaphylaxis including response to epinephrine. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2006; 140(1): 27–9

Schmitt JA, Riedel WJ, Vuurman EF, et al. Modulation of the critical flicker fusion effects of serotonin reuptake inhibitors by concomitant pupillary changes. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002 Apr; 160(4): 381–6

Costagliola C, Mastropasqua L, Capone D, et al. Effect of fluoxetine on intraocular pressure in the rabbit. Exp Eye Res 2000 May; 70(5): 551–5

Tobin AB, Unger W, Osborne NN. Evidence for the presence of serotonergic neurons and receptors in the irisciliary body complex of the rabbit. J Neurosci 1988; 8: 3713–21

Chidlow G, Le Corre S, Osborne SS. Localization of 5-hydroxytryptamine1A and 5-hydroxytryptamine7 receptors in rabbit ocular and brain tissues. Neuroscience 1998; 87: 675–89

Osborne NN, Chidlow G. Do beta-adrenoceptors and serotonin 5-HT1A receptors have similar functions in the control of intraocular pressure in the rabbit? Ophthalmologica 1996; 210: 308–14

Tobin AB, Osborne NN. Evidence for the presence of serotonin receptors negatively coupled to adenylate cyclase in the rabbit iris-ciliary body. J Neurochem 1989; 53: 686–91

Preskorn SH. Comparison of the tolerability of bupropion, fluoxetine, imipramine, nefazodone, paroxetine, sertraline and venlafaxine. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56 Suppl. 6: 12–21

Trindade E, Menon D, Topfer LA, et al. Adverse effects associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants: a meta-analysis. CMAJ 1998; 159: 1245–52

Beasley Jr CM, Koke SC, Nilsson ME, et al. Adverse events and treatment discontinuations in clinical trials of fluoxetine in major depressive disorder: an updated meta-analysis. Clin Ther 2000; 22: 1319–30

Thompson C, Peveler RC, Stephenson D, et al. Compliance with antidepressant medication in the treatment of major depressive disorder in primary care: a randomized comparison of fluoxetine and a tricyclic antidepressant. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157: 338–43

Ahmad S. Fluoxetine and glaucoma [letter]. DICP 1991; 25: 436

Kirwan JF, Subak-Sharpe I, Teimory M. Bilateral acute angle closure glaucoma after administration of paroxetine [letter]. Br J Ophthalmol 1997; 81: 252

Lewis CF, DeQuardo JR, DuBose C, et al. Acute angle-closure glaucoma and paroxetine. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58: 123–4

Eke T, Bates AK. Acute angle closure glaucoma associated with paroxetine [letter]. BMJ 1997; 314: 1387

Bennett HG, Wyllie AM. Paroxetine and acute angle closure glaucoma. Eye 1999; 13: 691–2

Browning AC, Reck AC, Chisholm IH, et al. Acute angle closure glaucoma presenting in a young patient after administration of paroxetine. Eye 2000; 14: 406–8

Jimenez-Jimenez FJ, Orti-Pareja M, Zurdo JM. Aggravation of glaucoma with fluvoxamine. Ann Pharmacother 2001; 35: 1565–6

Adverse Drug Reactions Advisory Committee (ADRAC). SSRIs and increased intraocular pressure [abstract]. Aust Adv Drugs Reac Bull 2001; 20(1): 3

Saletu B, Grünberger J. Drug profiling by computed electroencephalography and brain maps, with special consideration of sertraline and its psychometric effects. J Clin Psychiatry 1988; 49: 59–71

Deijen JB, Loriaux SM, Orlebeke JF, et al. Effects of paroxetine and maprotiline on mood, perceptual-motor skills and eye movements in healthy volunteers. J Psychopharmacol 1989; 3: 148–55

Ramaekers JG, Muntjewerff ND, O’Hanlon JF. A comparative study of acute and subchronic effects of dothiepin, fluoxetine and placebo on psychomotor and actual driving performance. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1995; 39: 397–404

Tripathi RC, Tripathi BJ, Haggerty C. Drug-induced glaucomas: mechanism and management. Drug Saf 2003; 26(11): 749–67

Ritch R, Krupin T, Henry C, et al. Oral imipramine and acute angle closure glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 1994; 112(1): 67–8

Lowe RF. Amitriptyline and glaucoma. Med J Aust 1966; 2(11): 509–10

Hyams SW, Keroub C. Glaucoma due to diazepam. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 134: 447–8

Sankar PS, Pasquale LR, Grosskreutz CL. Uveal effusion and secondary angle-closure glaucoma associated with topiramate use. Arch Ophthalmol 2001; 119: 1210–1

Fraunfelder FW, Fraunfelder FT, Keates EU. Topiramate-associated acute, bilateral, secondary angle-closure glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2004; 111: 109–11

Banta JT, Hoffman K, Budezn L, et al. Presumed topiramate-induced bilateral acute angle-closure glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 2001; 132: 112–4

Thambi L, Kapcala LP, Chambers W, et al. Topiramate-associated secondary angle-closure glaucoma: a case series. Arch Ophthalmol 2002; 120: 1210–1

Croos R, Thirumalai S, Hassan S, et al. Citalopram associated with acute angle-closure glaucoma: case report [letter]. BMC Ophthalmol 2005; 5: 23

Massaoutis P, Goh D, Foster PJ. Bilateral symptomatic angle closure associated with a regular dose of citalopram, an SSRI antidepressant. Br J Ophthalmol 2007; 91(8): 1086–7

Zelefsky JR, Fine HF, Rubinstein VJ, et al. Escitalopram-induced effusions and bilateral angle closure glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 2006; 141(6): 1144–7

Levy J, Tessler Z, Klemperer I, et al. Late bilateral acute angle-closure glaucoma after administration of paroxetine in a patient with plateau iris configuration. Can J Ophthalmol 2004; 39(7): 780–1

Costagliola C, Mastropasqua L, Steardo L, et al. Fluoxetine oral administration increases intraocular pressure [letter]. Br J Ophthalmol 1996; 80: 678

Shahzad S, Suleman MI, Shahab H, et al. Cataract occurrence with antipsychotic drugs. Psychosomatics 2002 Sep–Oct; 43(5): 354–9

Boet DJ. Toxic effects of phenothiazines on the eye. Doc Ophthalmol 1970; 28(1): 1–69

Gowdey CW, Coleman LM, Crawford EM. Ocular changes and phenothiazine derivatives in long-term residents of a mental retardation center. Psychiatr J Univ Ott 1985; 10(4): 248–53

Thaler JS, Curinga R, Kiracofe G. Relation of graded ocular anterior chamber pigmentation to phenothiazine intake in schizophrenics: quantification procedures. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1985; 62(9): 600–4

Barnes GJ, Cameron ME. Skin and eye changes associated with chlorpromazine therapy. Med J Aust 1966; 1(12): 478–81

Zigman S, Datiles M, Torczynski E. Sunlight and human cataracts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1979; 18(5): 462–7

Feldman PE, Frierson BD. Dermatological and ophthalmological changes associated with prolonged chlorpromazine therapy. Am J Psychiatry 1964 Aug; 121: 187–8

Greiner AC, Berry K. Skin pigmentation and corneal and lens opacities with prolonged chlorpromazine therapy. CMAJ 1964 Mar 14; 90: 663–5

Satanove A. Pigmentation due to phenothiazines in high and prolonged dosage. JAMA 1965; 191(4): 263–8

Siddall JR. Ocular complications related to phenothiazines. Dis Nerv Syst 1968; 29(3) Suppl.: 10–3

Buffaloe WJ, Johnson AW, Sandifer Jr MG. Total dosage of chlorpromazine and ocular opacities. Am J Psychiatry 1967; 124: 250–1

Wetterholm DH, Snow HL, Winter FC, et al. A clinical study of pigmentary changes in cornea and lens in chronic chlorpromazine therapy. Arch Ophthalmol 1965; 74: 55–6

Seroquel® (quetiapine) [package insert]. Wilmington (DE); Zeneca Pharmaceuticals, 2001

Stip E, Boisjoly H. Quetiapine: are we overreacting in our concern about cataracts (the beagle effect) [abstract]? Can J Psychiatry 1999 Jun; 44(5): 503

Siddall JR. Ocular toxic changes associated with chlorpromazine and thioridazine. Can J Ophthalmol 1966; 1: 190–8

Hagopian Y, Stratton DB. Five cases of pigmentary retinopathy associated with thioridazine administration. Am J Psychiatry 1966; 123: 97–100

Meredith TA, Aaberg TM, Willerson WD. Progressive chorioretinopathy after receiving thioridazine. Arch Ophthalmol 1978; 96: 1172–6

Legros J, Rosner I, Berger C. Ocular effects of chlorpromazine and oxypertine on beagle dogs. Br J Ophthalmol 1971 Jun; 55(6): 407–15

Kashi S, Takahashi M, Mandai M, et al. Protective action of dopamine against glutamate neurotoxicity in the retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1994 Feb; 35(2): 685–95

Lobefalo L, Rapinese M, Altobelli E, et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer and macular thickness in adolescents with epilepsy treated with valproate and carbamazepine. Epilepsia 2006 Apr; 47(4): 717–9

Nielsen NV, Syversen K. Possible retinotoxic effect of carbamazepine. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1986; 64(3): 287–90

Verrotti A, Lobefalo L, Tocco AM, et al. Color vision and macular recovery time in epileptic adolescents treated with valproate and carbamazepine. Eur J Neurol 2006; 13(7): 736–41

Alkawi A, Kattah JC, Wyman K. Downbeat nystagmus as a result of lamotrigine toxicity. Epilepsy Res 2005; 63(2–3): 85–8

Sener EC, Kiratli H. Presumed sertraline maculopathy. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2001 Aug; 79(4): 428–30

Litovitz GL. Amitriptyline and contact lenses [letter]. J Clin Psychiatry 1984; 45: 188

Goode DJ. Increased palpebral aperture in a patient receiving amitriptyline. Am J Psychiatry 1977; 134: 1043–4

Hughes MS, Lessell S. Trazodone-induced palinopsia. Arch Ophthalmol 1990; 108: 399–400

Adam OR, Jankovic J. Treatment of dystonia. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2007; 13Suppl. 3: S362–8

Tan CH, Chiang PC, Ng LL, et al. Oculogyric spasm in Asian psychiatric in-patients on maintenance medication [abstract]. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166(1): 117

Faulks RS, Gilmore JH, Jensen EW, et al. Risperidone-induced dystonic reaction [letter]. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153(4): 577

Rosenhagen MC, Schmidt U, Winkelmann J, et al. Olanzapine-induced oculogyric crisis [letter]. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006; 26(4): 431

Desarkar P, Das A, Sinha VK. Olanzapine-induced oculogyric crisis [letter]. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2006; 40(4): 374

Uzun O, Doruk A. Tardive oculogyric crisis during treatment with clozapine: report of three cases. Clin Drug Investig 2007; 27(12): 861–4

Fountoulakis KN, Siamouli M, Kantartzis S, et al. Acute dystonia with low dosage aripiprazole in Tourette’s disorder. Ann Pharmacother 2006; 40(4): 775–7

Berchou RC, Rodin EA. Carbamazepine-induced oculogyric crisis. Arch Neurol 1979; 36(8): 522–3

Arnstein E. Oculogyric crisis: a distinct toxic effect of carbamazepine. J Child Neurol 1986; 1(3): 289–90

Gorman M, Barkley GL. Oculogyric crisis induced by carbamazepine. Epilepsia 1995; 36(11): 1158–60

Henry EV. Oculogyric crisis and carbamazepine [letter]. Arch Neurol 1980; 37(5): 326

Leo RJ. Movement disorders associated with the serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57(10): 449–54

Gerber PE, Lynd LD. Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor-induced movement disorders. Ann Pharmacother 1998; 32(6): 692–8

Stapleton JM, Guthrie S, Linnoila M. Effects of alcohol and other psychotropic drugs on eye movements: relevance to traffic safety. J Stud Alcohol 1986; 47: 426–32

Hommer DW, Matsuo V, Wolkowitz O, et al. Benzodiazepine sensitivity in normal human subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43: 542–52

Bittencourt PRM, Wade P, Smith AT, et al. Benzodiazepines impair smooth pursuit eye movements. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1983; 15: 259–62

Khouzam HR, Highet VS. A review of clonazepam use in neurology. Neurobiologist 1997; 3: 120–7

Rucker JC. Current treatment of nystagmus. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2005; 7(1): 69–77

Young YH, Huang TW. Role of clonazepam in the treatment of idiopathic downbeat nystagmus. Laryngoscope 2001; 111(8): 1490–3

Coppeto JR, Monteiro MLR, Lessell S. Downbeat nystagmus: long-term therapy with moderate-dose lithium carbonate. Arch Neurol 1983; 40: 754–5

Williams DP, Troost BT, Rogers J. Lithium-induced downbeat nystagmus. Arch Neurol 1988; 45: 1022–3

Rosenberg ML. Permanent lithium-induced down-beating nystagmus [letter]. Arch Neurol 1989; 46: 839

Halmagyi GM, Lessell I, Curthoys IS, et al. Lithium-induced downbeat nystagmus. Am J Ophthalmol 1989; 107: 664–74

Chrousos GA, Cowdry R, Schuelein M, et al. Two-cases of downbeat nystagmus and oscillopsia associated with carbamazepine. Am J Ophthalmol 1987; 103: 221–4

Mullally WJ. Carbamazepine-induced ophthalmoplegia [letter]. Arch Neurol 1982; 39: 64

Besag FMC, Berry DJ, Pool F, et al. Carbamazepine toxicity with lamotrigine: pharmacokinetic or pharmaco-dynamic interactions? Epilepsia 1998; 39: 183–7

Loiseau P. Tolerability of newer and older anticonvulsants: a comparative review. CNS Drugs 1996; 6: 148–66

Segal RL, Rosenblatt S, Eliasoph I. Endocrine exophthal-mos during lithium therapy of manic-depressive disease. N Engl J Med 1973; 289: 136–8

Lobo A, Pilek E, Stokes PE. Papilledema following therapeutic dosages of lithium carbonate. J Nerv Ment Dis 1978; 166: 526–9

Verrotti A, Lobefalo L, Priolo T, et al. Colour vision in epileptic adolescents treated with valproate and carbamazepine. Seizure 2004; 13: 411–7

Sorri I, Rissanen E, Mantyjarvi M, et al. Visual function in epilepsy patients treated with initial valproate mono-therapy. Seizure 2005 Sep; 14(6): 367–70

Steinhoff BJ, Freudenthaler N, Paulus W. The influence of established and new antiepileptic drugs on visual perception: II. A controlled study in patients with epilepsy under long-term antiepileptic medication. Epilepsy Res 1997; 29: 49–58

Nousiainen I, Kalviainen R, Mantyjarvi M. Colour vision in epilepsy patients treated with vigabatrin or carbamazepine monotherapy. Ophthalmology 2000; 107: 884–8

Paulus W, Schwarz G, Steinhoff BJ. The effect of antiepileptic drugs on visual perception in patients with epilepsy. Brain 1996; 119: 539–49

Mecarelli O, Rinalduzzi S, Accornero N. Changes in colour vision after a single dose of vigabatrin or carbamazepine in healthy volunteers. Clin Neuropharmacol 2001; 24: 23–6

Steinhoff B, Freudenthaler N, Paulus W. The influence of established and new antiepileptic drugs on visual perception: I. A placebo-controlled, double blind, single-dose study in healthy volunteers. Epilepsy Res 1997; 29: 35–47

Giersch A, Speeg-Schatz C, Tondre M, et al. Impairment of contrast sensitivity in long-term lorazepam users. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006 Jul; 186(4): 594–600

Klein BE, Klein R, Knudtson MD, et al. Associations of selected medications and visual function: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Br J Ophthalmol 2003 Apr; 87(4): 403–8

Leung AT, Cheng AC, Chan WM, et al. Chlorpromazine-induced refractile corneal deposits and cataract. Arch Ophthalmol 1999; 117(12): 1662–3

Acknowledgements

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this review. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Richa, S., Yazbek, JC. Ocular adverse effects of common psychotropic agents. CNS Drugs 24, 501–526 (2010). https://doi.org/10.2165/11533180-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11533180-000000000-00000