Spondyloarthritis: diagnosis and management: summary of NICE guidance

BMJ 2017; 356 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j839 (Published 01 March 2017) Cite this as: BMJ 2017;356:j839

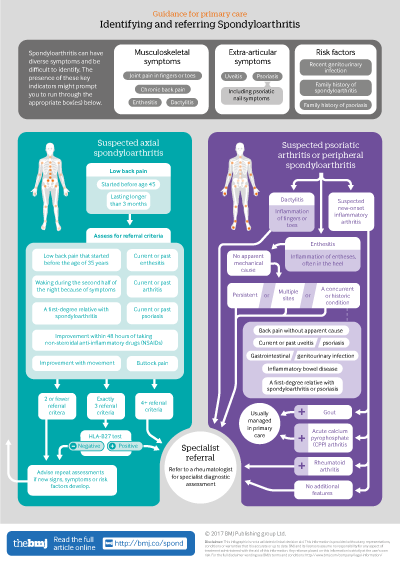

Infographic available

Click here for a visual overview of how to assess people with suspected spoondyloarthritis in primary care, and when to refer them to a rheumatology specialist

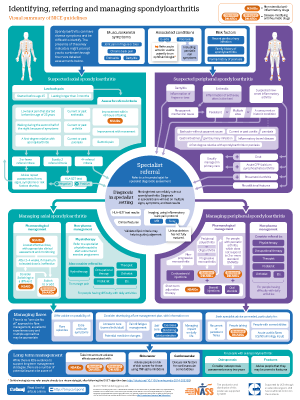

Infographic poster available

Click here for an A2 poster version of the infographic, covering both referral and management of spondyloarthritis

- Katherine McAllister, technical analyst1,

- Nicola Goodson, senior lecturer in rheumatology2,

- Louise Warburton, GP with special interest in rheumatology, lead for Telford Musculoskeletal Service, associate medical director, senior lecturer in primary care3 4,

- Gabriel Rogers, technical adviser in health economics1

- 1National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Manchester M1 4BT, UK

- 2Rheumatology Research group, Department of Musculoskeletal Biology I, Institute of Ageing and Chronic Disease, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 3BX, UK

- 3Shropshire Community Health NHS Trust, Shrewsbury SY3 8XL, UK

- 4Department of Primary Care and Health Sciences, Keele University, Staffordshire ST5 5BG, UK

- Correspondence to: G Rogers Gabriel.Rogers{at}nice.org.uk

What you need to know

Spondyloarthritis is often missed in non-specialist settings, leading to substantial delays in diagnosis and treatment

Axial spondyloarthritis affects similar numbers of women and men, is not always apparent on plain x ray, and occurs in people who are seronegative for human leucocyte antigen B27 (HLA-B27)

No single test can reliably diagnose or rule out spondyloarthritis—decisions cannot rest on an individual sign, symptom, or test result

Assess people with low back pain that started before the age of 45 years and has lasted for longer than 3 months for axial spondyloarthritis

Refer people with unexplained dactylitis, new onset inflammatory arthritis, or persistent non-mechanical enthesitis in multiple sites or in conjunction with other risk factors to a rheumatologist for investigation of peripheral spondyloarthritis

Spondyloarthritis encompasses a group of inflammatory conditions with some shared features, including extra-articular manifestations that may occur at initial presentation or later. The guideline distinguishes between peripheral and axial disease (see box 1).

Box 1: Types of spondyloarthritis

Predominantly axial

Ankylosing spondylitis (radiographic axial spondyloarthritis)

Non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis

Predominantly peripheral

Psoriatic arthritis

Reactive arthritis (typically following gastrointestinal or genitourinal infections, including (but not limited to) Campylobacter, Chlamydia, Salmonella, Shigella, or Yersinia)

Enteropathic arthritis (associated with comorbid inflammatory bowel disease)

Note: Predominantly axial spondyloarthritis may also have peripheral features, and vice versa

Healthcare professionals in non-specialist settings frequently fail to recognise signs and symptoms of spondyloarthritis. Axial presentations of spondyloarthritis are often misdiagnosed as mechanical low back pain, leading to delays in access to effective treatments. There is an average delay of 8.5 years between symptom onset and diagnosis, with only around 15% of cases receiving a diagnosis within three months of initial presentation.1 Contrary to common misconceptions, axial spondyloarthritis affects similar numbers of women and men, is not always apparent on plain x ray, and occurs in people who are seronegative for human leucocyte antigen B27 (HLA-B27). Peripheral presentations are often seen as unrelated joint or tendon problems and can be misdiagnosed because problems can move between joint areas. Even in people with well known comorbidities (such as psoriasis), peripheral spondyloarthritis may be missed.

This guideline seeks to raise awareness of the features of spondyloarthritis and provide clear advice on what action to take when people with signs and symptoms first present in non-specialist healthcare settings. This guideline also provides advice on pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions and surgery available to people with spondyloarthritis, and advice on how care should be organised across healthcare settings and what information and support should be provided.

This article summarises the most recent recommendations from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline for the diagnosis and management of spondyloarthritis in people aged 16 years and above.2 Recommendations and the clinical pathway are available via the NICE website.

What’s new in this guidance

A list of the important criteria that raise suspicion of axial or peripheral spondyloarthritis

Structured criteria for referral to specialist rheumatology services for people with chronic low back pain, suspected psoriatic arthritis and other peripheral spondyloarthritides, and acute anterior uveitis

Recommendations on the organisation of long term and cross-speciality care for people with spondyloarthritis

Recommendations

NICE recommendations are based on systematic reviews of best available evidence and explicit consideration of cost effectiveness. When minimal evidence is available, recommendations are based on the Guideline Development Group’s experience and opinion of what constitutes good practice. Evidence levels for the recommendations are given in italic in square brackets.

Methods

The Guideline Development Group (GDG) comprised a professor of cardiovascular medicine (non-specialist chair), three rheumatologists, a general practitioner, a rheumatology nurse specialist, a clinical pharmacist, a physiotherapist, and two lay members. Co-opted experts included an orthopaedic surgeon, an occupational therapist, a dermatologist, an ophthalmologist, two radiologists, and a gastroenterologist.

The guideline was developed using standard NICE guideline methodology (2012) (www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg6/chapter/introduction). The GDG developed clinical questions, collected and appraised clinical evidence, and evaluated the cost effectiveness of proposed interventions and management strategies through literature review and economic considerations where possible. Quality ratings of the evidence were based on GRADE methodology (www.gradeworkinggroup.org). These relate to the quality of the available evidence for assessed outcomes rather than the quality of the clinical study. Where standard methods could not be applied, a customised quality assessment was done. Stakeholder consultation was undertaken at both the scoping and development stages.

Definition of terms

Dactylitis—Inflammation of a whole digit, including joints, tendons and entheses

Enthesitis—Inflammation at the point at which a tendon attaches to a bone

HLA-B27—Human leucocyte antigen B27; a genetic marker associated with spondyloarthritis

DMARDs—Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (standard or biological)

Suspecting spondyloarthritis

No single test has been shown to have sufficient sensitivity or specificity to diagnose or rule out spondyloarthritis, and it is important that referral and diagnostic decisions are not made based on the presence or absence of any individual sign, symptom, or test result. Box 2 shows some of the main signs and symptoms that may raise suspicion of spondyloarthritis. When spondyloarthritis is suspected, the guideline gives criteria for deciding whether the person should be referred to rheumatology for specialist diagnostic assessment (see infographic).

Box 2: Suspecting spondyloarthritis

Recognise that spondyloarthritis can have diverse symptoms and be difficult to identify, which can lead to delayed or missed diagnoses

Signs and symptoms may be musculoskeletal (such as inflammatory back pain, enthesitis, and dactylitis) or extra-articular (such as uveitis and psoriasis (including psoriatic nail symptoms))

Risk factors include recent genitourinary infection and a family history of spondyloarthritis or psoriasis

[Based on very low to high quality evidence from diagnostic accuracy studies]

Referral criteria

Axial spondyloarthritis

If a person has low back pain that started before the age of 45 years and has lasted for longer than three months, refer the person to a rheumatologist for a spondyloarthritis assessment if four or more of the additional criteria in box 3 are also present. [Based on high quality evidence from diagnostic accuracy studies and a newly developed economic model]

If exactly three of the additional criteria in box 3 are present, perform an HLA-B27 test. If the test is positive, refer the person to a rheumatologist for spondyloarthritis assessment. [Based on high quality evidence from diagnostic accuracy studies and a newly developed economic model]

If the person does not meet the criteria for referral in box 3, but clinical suspicion of axial spondyloarthritis remains, advise the person to seek repeat assessments if any of the signs, symptoms, or risk factors listed in box 2 subsequently develop. This may be especially appropriate if the person has current or past inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis), psoriasis, or uveitis. [Based on the experience and opinion of the Guideline Development Group (GDG)]

Box 3: Axial spondyloarthritis referral criteria for people who have low back pain that started before the age of 45 years which has lasted for longer than three months

Low back pain that started before the age of 35 years (more likely to be due to spondyloarthritis compared with low back pain that started between 35 and 44 years)

Waking during the second half of the night because of symptoms

Buttock pain

Improvement with movement

Improvement within 48 hours of taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

A first degree relative with spondyloarthritis

Current or past arthritis

Current or past enthesitis

Current or past psoriasis

Refer to a rheumatologist if four or more criteria are met. If exactly three are present, perform an HLA-B27 test and refer if the test is positive

Psoriatic arthritis and other peripheral spondyloarthritides

Urgently refer people with suspected new onset inflammatory arthritis to a rheumatologist for a spondyloarthritis assessment, unless rheumatoid arthritis, gout, or acute calcium pyrophosphate arthritis (“pseudogout”) is suspected. If rheumatoid arthritis is suspected, see referral for specialist treatment in the NICE guideline on rheumatoid arthritis in adults. [Based on the experience and opinion of the GDG]

Refer people with dactylitis to a rheumatologist for a spondyloarthritis assessment. [Based on very low to moderate quality evidence from diagnostic accuracy studies]

Refer people with enthesitis without apparent mechanical cause to a rheumatologist for a spondyloarthritis assessment if:

It is persistent or

It is in multiple sites or

Any of the following are also present:

Back pain without apparent mechanical cause

Current or past uveitis

Current or past psoriasis

Gastrointestinal or genitourinary infection

Inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis)

A first degree relative with spondyloarthritis or psoriasis

[Based on low to moderate quality evidence from diagnostic accuracy studies and the experience and opinion of the GDG]

Diagnosing spondyloarthritis

In specialist care settings, the diagnosis of spondyloarthritis will be based on several factors, including clinical features, HLA-B27 test results, imaging (x ray and magnetic resonance imaging), and may be assisted by the use of validated spondyloarthritis criteria. X ray is not an appropriate first line imaging investigation in people whose skeleton has not fully matured. Features of axial spondyloarthritis can be missed on traditional spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which often fails to include the sacroiliac joints and lacks the STIR weighted images required to detect bone oedema.

Managing spondyloarthritis

Box 4 summarises the main pharmacological and non-pharmacological management options for spondyloarthritis.

Box 4: Pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of spondyloarthritis

Axial spondyloarthritis

Pharmacological management

First line treatment is the lowest effective dose of NSAID, with appropriate clinical assessment and monitoring

If the maximum tolerated dose for 2-4 weeks does not provide adequate relief, consider switching to another NSAID or using biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) (use of biological DMARDs for axial spondyloarthritis has been the subject of NICE technology appraisals3 4)

Non-pharmacological management

People with axial spondyloarthritis should be referred to a specialist physiotherapist to start a structured exercise programme

Consider referral to hydrotherapy for pain or other specialist therapists (occupational therapist, therapist, orthotist, podiatrist, etc) for people who have difficulties with everyday activities

Psoriatic arthritis and other peripheral spondyloarthritides

Pharmacological management

First line treatment options for peripheral spondyloarthritis include corticosteroid injections for non-progressive monoarthritis and standard DMARDs for peripheral polyarthritis, oligoarthritis, and progressive monoarthritis

Biological DMARDs are an option for treating psoriatic arthritis that has not responded to two standard DMARDs (use of biological DMARDs for psoriatic arthritis has been the subject of NICE technology appraisals5 6 7 8)

Short term NSAIDs at the lowest effective dose, steroid injections, or short term oral steroid therapy may be used as an adjunct to standard or biological DMARDs

Non-pharmacological management

Consider referrals to specialist therapists (physiotherapist, occupational therapist, therapist, orthotist, podiatrist, etc) for people who have difficulties with everyday activities

While NSAIDs may be initiated in primary care before confirmation of diagnosis, standard or biological DMARDs will be initiated in specialist settings. Ongoing monitoring of pharmacological therapies, and changes to these during flare episodes, can take place in primary or secondary care as appropriate. The GDG agreed that no “one size fits all” guidance could be provided for optimal flare management, as patients’ experiences vary and multiple approaches may be appropriate; however, the guideline sets out overarching principles of effective care.

Managing flares

Advise people with spondyloarthritis about the possibility of experiencing flare episodes and extra-articular symptoms. [Based on the experience and opinion of the GDG]

Consider developing a flare management plan that is tailored to the person’s individual needs, preferences and circumstances. [Based on the experience and opinion of the GDG]

When discussing any flare management plan, provide information on:

Access to care during flares (including details of a named person to contact such as a specialist rheumatology nurse)

Self care (for example, exercises, stretching, and joint protection)

Pain and fatigue management

Potential changes to medicines

Managing the impact on daily life and ability to work.

[Based on the experience and opinion of the GDG]

When managing flares in primary care, seek advice from specialist care as needed, particularly for people who:

Have recurrent or persistent flares

Are taking biological DMARDs

Have comorbidities that may affect treatment or management of flares.

[Based on the experience and opinion of the GDG]

Long term complications

Limited evidence was available for evaluating the long term complications of either spondyloarthritis or its pharmacological treatments, and therefore a standardised long term care plan could not be developed. However, the guideline highlights specific issues and emphasises the need for a coordinated care pathway.

Take into account the adverse effects associated with NSAIDs, standard DMARDs, and biological DMARDs when monitoring spondyloarthritis in primary care. [Based on very low quality evidence from cohort studies]

Advise people that there may be a greater risk of skin cancer in people treated with tumour necrosis factor (TNF) alpha inhibitors. [Based on very low quality evidence from cohort studies]

Discuss risk factors for cardiovascular comorbidities with all people with spondyloarthritis. [Based on very low quality evidence from cohort studies]

Consider regular osteoporosis assessments (every two years) for people with axial spondyloarthritis. Be aware that bone mineral density measures may be elevated on spinal dual energy x ray absorptiometry (DEXA) due to the presence of syndesmophytes and ligamentous calcification, whereas hip measurements may be more reliable. [Based on the experience and opinion of the GDG]

Advise people with axial spondyloarthritis that they may be prone to fractures, and should consult a healthcare professional after a fall or physical trauma, particularly in the event of increased musculoskeletal pain. [Based on the experience and opinion of the GDG]

Organisation of care

Healthcare commissioners should ensure that local arrangements are in place to coordinate care for people across primary and secondary (specialist) care. These should cover:

Prescribing NSAIDs and standard DMARDs

Monitoring NSAIDs, standard DMARDs and biological DMARDs

Managing flares

Ensuring prompt access to specialist rheumatology care when needed

Ensuring prompt access to other specialist services to manage comorbidities and extra-articular symptoms

[Based on the experience and opinion of the GDG]

Ensure that people with spondyloarthritis have access to specialist care in primary or secondary care settings throughout the disease course to ensure optimal long term management. [Based on the experience and opinion of the GDG]

Guidelines into practice

This guideline has defined new referral criteria for both axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis from primary care into specialist care

Reflect—To what extent are you aware of the signs and symptoms of both axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis, and why these may be missed?

Project—How many people in your care with low back pain that started before the age of 45 years and has lasted for longer than three months have been assessed using the axial spondyloarthritis criteria?

Project—Are appropriate procedures in place to ensure people with spondyloarthritis can access specialist care when it is needed?

Is there access to HLA-B27 testing within your local health economy?

Future research

The following were identified as important questions for future research:

What are the optimal referral criteria for people with suspected axial spondyloarthritis?

What is the incidence of long term complications—in particular osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome—in people with spondyloarthritis, and how does this compare with the general population? Are any specific spondyloarthritis features or risk factors associated with the incidence and outcomes of these complications?

What is the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of educational interventions for healthcare professionals in order to increase the number of prompt diagnoses of spondyloarthritis?

What is the comparative effectiveness and cost effectiveness of standard DMARDs for managing peripheral spondyloarthritis, and is this effectiveness affected by differences in dose escalation protocols?

What is the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of biological DMARDs in people with persistent peripheral spondyloarthritis (excluding psoriatic arthritis) or undifferentiated spondyloarthritis?

How patients were involved in the creation of this article

No patients were involved in the creation of this summary. However, committee members involved in this guideline included lay members who contributed to the formulation of the recommendations summarised here. The views of multiple patient organisations were sought for both the original scope of the guideline and its draft recommendations.

Footnotes

The members of the Guideline Development Group were Gary McVeigh (guideline chair), Issak Bhojani (until August 2015), David Chandler, Debbie Cook, Charlotte Davis, Nicola Goodson, Tina Hawkins, Philip Helliwell (until October 2014), Amanda Isdale, Carol McCrum, Jon Packham, Claire Strudwicke (until May 2015), and Louise Warburton. Co-opted members were Alexander DL Baker, Nicky Bassett-Burr, Seau Cheung, Alastair Denniston, Philip O’Connor, Tim Orchard, Winston Rennie, and Debajit Sen.

The members of the NICE Centre for Guidelines team were Sara Buckner (February to May 2015), Jemma Dean, Maggie Derry (until September 2015), Sue Ellerby, Nicole Elliot (until June 2014), Lucy Hoppe (June to August 2015), Rachel Houten (until December 2014 and from September 2015 to July 2016), Holly Irwin (September to November 2015), Neel Jain (July to August 2015), Katherine McAllister (from September 2014), Hugh McGuire (until December 2015), Vonda Murray (from November 2015), Vonda Murray (from November 2015), Joshua Pink (from February 2016), Robby Richey (August 2015 to January 2016), Gabriel Rogers, Sue Spiers (from June 2014), Sharlene Ting (January to March 2015), Steven Ward (December 2014 to September 2015).

Contributors: All authors contributed to the conception and drafting of this article, and to revising it critically. They have all approved this version. GR is guarantor.

Funding: During the development of this work, GR and KM were both employees of NICE, which is commissioned and funded by the Department of Health to develop clinical guidelines. No authors received specific funding to write this summary.

Competing interests: The authors all declare that they have no conflicts of interest, based on NICE's policy on conflicts of interests (www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/Who-we-are/Policies-and-procedures/code-of-practice-for-declaring-and-managing-conflicts-of-interest.pdf).